Atrial Fibrillation Occurring During Acute Hospitalization

Last Updated: October 29, 2024

Atrial Fibrillation: Once and Perhaps Forever?

Clinicians from all specialties will commonly encounter a patient who develops a first episode of atrial fibrillation (AF) in the hospital, whether during acute illness or associated with surgery 1. The AHA Scientific Statement: Atrial Fibrillation Occurring During Acute Hospitalization provides important guidance to clinicians on the management of AF in these settings and the future implications this has for the patient.

How should atrial fibrillation be managed in the hospitalization?

Managing the acute episode of AF during a hospitalization has three fundamental steps. First managing any hemodynamic compromise, second making an initial decision between a rate control strategy and a rhythm control strategy, and finally addressing stroke risk.

As emphasized in this document and the current American Heart Association Advanced Cardiac Life Support algorithms, acute development of AF associated with significant hemodynamic compromise should be treated with timely direct current cardioversion 2.

Once this issue has been addressed, the decision on whether to pursue an initial rate control strategy or rhythm control strategy depends on multiple factors but often a rate control strategy is initially pursued to allow time to 1) address triggers associated with the arrhythmia, 2) provide an opportunity for the AF to resolve spontaneously as the patient progresses through their acute hospitalization, and 3) fully assess stroke risk. If transition to a rhythm control strategy is decided upon in the acute setting, it is important to evaluate and manage any potential incremental stroke risk, particularly if cardioversion is required. The decision on whether or not to pursue rhythm control in the hospital is nuanced and will depend on the specific reason for hospitalization, the suspected triggers, and patient symptoms and comorbidities.

Finally, the primary clinicians taking care of the patient must evaluate the acute stroke risk, stroke risk in the immediate post hospitalization period, and ensure that the patient has appropriate follow-up that will evaluate future stroke risk once the patient is discharged. Without question this is the most important step for AF management that develops during hospitalization.

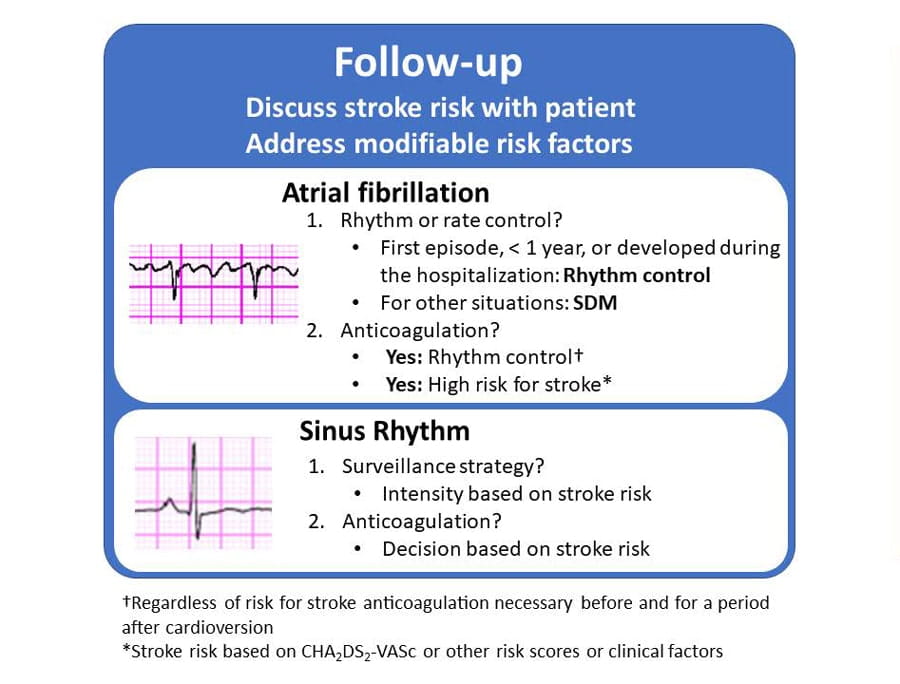

After discharge, what next?

The transition from the hospital to the first outpatient visit is commonly a time when suboptimal patient management may occur, and this is particularly important in patients who develop AF during hospitalization 3,4. In the patient who remains in AF after discharge, it is critical to have a follow-up plan in place that will review whether a rhythm control strategy will be pursued. Persistent AF despite resolution of the acute triggers associated with hospitalization suggests that the AF will likely be a significant longer-term issue for the patient. New evidence consistently shows that a rhythm control strategy is more effective and associated with improved outcomes in the patient with recently identified AF (< 1year) 5. If this is a first episode of AF or the patient developed AF in the hospital setting, a rhythm control strategy with cardioversion is appropriate. If a rhythm control strategy is pursued anticoagulation should be maintained for at least four weeks after return to sinus rhythm and even longer if the patient has a high risk for stroke based on comorbidities and other factors such as age. It is also important to remember that restoration of sinus rhythm with cardioversion does not necessarily mean chronic antiarrhythmic therapy or catheter ablation. In the EAST AF Net 4 trial, which demonstrated an improvement in the combined outcome of cardiovascular death, stroke, or hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome or heart failure in AF patients randomized to an early rhythm control strategy compared to usual care. While antiarrhythmic medications were used in many patients initially, at two-year follow-up a third of patients were not on antiarrhythmic drugs nor had undergone catheter ablation 5.

In the patient who is in sinus rhythm at follow-up, the patient’s underlying risk for stroke and likelihood for developing AF should be evaluated. Multiple studies have demonstrated that patients who develop AF in the hospital have a higher likelihood of developing AF or experiencing a future stroke 6,7. In patients with higher stroke risk, increased vigilance, whether through traditional health care technology or emerging technology such as artificial intelligence and wearables may be valuable for early identification of recurrent AF.

However, regardless of whether the patient is in sinus rhythm or AF at follow-up, a frank discussion with the patient about the natural history of AF and risk of stroke is necessary. In addition, addressing modifiable risk factors such such as high blood pressure control, sleep apnea, smoking, obesity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and alcohol consumption are critical to potentially reduce future episodes of atrial fibrillation (8). The message of the document is clear for long-term patient care. Remember the 2 M’s: Monitor (and manage) the heart rhythm and institute lifestyle Modifications.

Citation

Chyou JY, Barkoudah E, Dukes JW, Goldstein LB, Joglar JA, Lee AM, Lubitz SA, Marill KA, Sneed KB, Streur MM, Wong GC, Gopinathannair R; on behalf of the American Heart Association Acute Cardiac Care and General Cardiology Committee, Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, and Clinical Pharmacology Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Stroke Council. Atrial fibrillation occurring during acute hospitalization: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association [published online ahead of print March 13, 2023]. Circulation. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001133

References

- McIntyre WF, Um KJ, Cheung CC, Belley-Côté EP, Dingwall O, Devereaux PJ, Wong JA, Conen D, Whitlock RP, Connolly SJ, Seifer CM, Healey JS. Atr ial fibrillation detected initially during acute medical illness: A systematic review. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2019 Mar;8(2):130-141.

- Panchal AR, Bartos JA, Cabañas JG, Donnino MW, Drennan IR, Hirsch KG, Kudenchuk PJ, Kurz MC, Lavonas EJ, Morley PT, O'Neil BJ, Peberdy MA, Rittenberger JC, Rodriguez AJ, Sawyer KN, Berg KM; Adult Basic and Advanced Life Support Writing Group. Part 3: Adult Basic and Advanced Life Support: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2020 Oct 20;142(16_suppl_2):S366-S468.

- Burke RE, Whitfield EA, Hittle D, Min SJ, Levy C, Prochazka AV, Coleman EA, Schwartz R, Ginde AA. Hospital Readmission From Post-Acute Care Facilities: Risk Factors, Timing, and Outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016 Mar 1;17(3):249-55

- Abadie BQ, Hansen B, Walker J, Deyo Z, Biese K, Armbruster T, Sears SF, Tuttle H, Sadaf MI, Gehi AK. An Atrial Fibrillation Transitions of Care Clinic Improves Atrial Fibrillation Quality Metrics. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2020 Jan;6(1):45-52

- Kirchhof P, Camm AJ, Goette A, Brandes A, Eckardt L, Elvan A, Fetsch T, van Gelder IC, Haase D, Haegeli LM, Hamann F, Heidbüchel H, Hindricks G, Kautzner J, Kuck KH, Mont L, Ng GA, Rekosz J, Schoen N, Schotten U, Suling A, Taggeselle J, Themistoclakis S, Vettorazzi E, Vardas P, Wegscheider K, Willems S, Crijns HJGM, Breithardt G; EAST-AFNET 4 Trial Investigators. Early Rhythm-Control Therapy in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2020 Oct 1;383(14):1305-1316

- Melduni RM, Schaff HV, Bailey KR, Cha SS, Ammash NM, Seward JB and Gersh BJ. Implications of new-onset atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery on long-term prognosis: a community-based study. American heart journal. 2015;170:659-68.

- Wang EY, Hulme OL, Khurshid S, Weng LC, Choi SH, Walkey AJ, Ashburner JM, McManus DD, Singer DE, Atlas SJ, Benjamin EJ, Ellinor PT, Trinquart L and Lubitz SA. Initial Precipitants and Recurrence of Atrial Fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020;13:e007716.

- Chung MK, Eckhardt LL, Chen LY, Ahmed HM, Gopinathannair R, Joglar JA, Noseworthy PA, Pack QR, Sanders P, Trulock KM; American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee and Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Secondary Prevention Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health. Lifestyle and Risk Factor Modification for Reduction of Atrial Fibrillation: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020 Apr 21;141(16):e750-e772

Science News Commentaries

-- The opinions expressed in this commentary are not necessarily those of the editors or of the American Heart Association --

Pub Date: Monday, Mar 13, 2023

Author: Fred Kusumoto MD

Affiliation: Professor of Medicine, Associate Dean Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine